Partimenti Tools in Developing Musical Memory

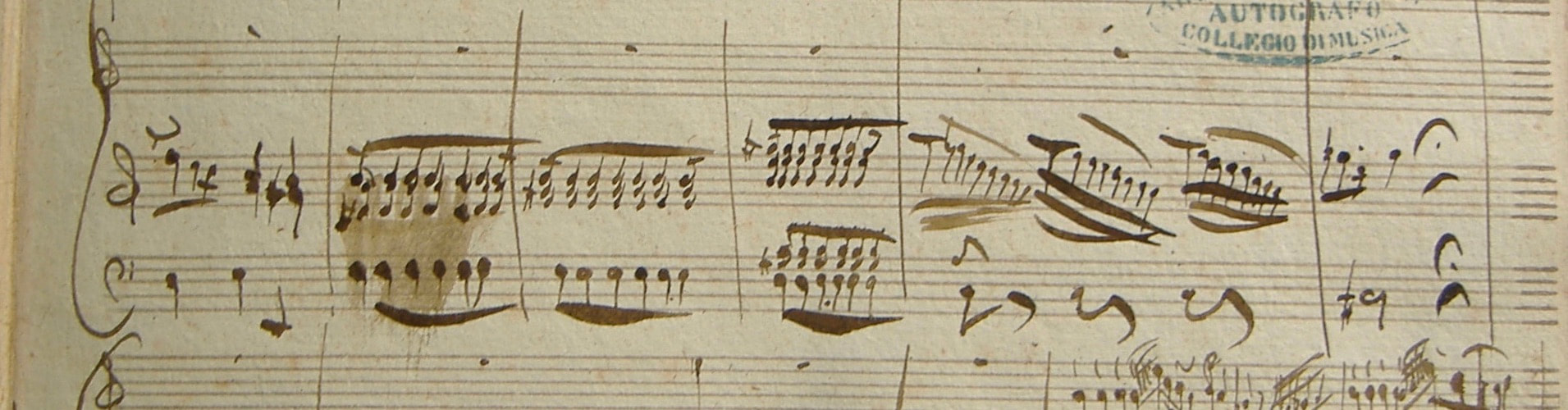

Robert Gjerdingen, music studies, recently published Music in the Galant Style (Oxford, 2007), in which he explores the "Italian School" of music, bringing to light one of the secrets of Neapolitan success: the instructional bass or partimento. Given just the bass part to an imaginary ensemble of voices or instrumentalists, a young boy in the conservatory would sit at a keyboard and play all the parts as if they were written out before him. To accomplish this magic, these young musicians needed to train their memories and imaginations. They practiced a non-verbal form of mental discipline that, when mastered, allowed them to compose sonatas or symphonies with the same facility that might characterize a master jazz musician today.

European court musicians were trained in partimenti, or instructional basses, from the late 1600s until the early 1800s. Partimenti had their greatest influence first in Italian conservatories, especially at Naples, and then later at the Paris Conservatory, where the principles of the "Italian school" continued to be taught far into the twentieth century. Because learning the Italian style of music was a priority for almost any eighteenth-century musician, many well-known non-Italian composers, including Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Mozart, also studied or taught partimenti.

The oldest Italian conservatories were not established to conserve music. They were charitable religious institutions where orphans and foundlings would be taught trades. In a society where family connections and social rank were all-important, an orphan needed a marketable skill in order to make his way in the world. It was not enough to learn "about" music. The child needed to become fluent in the courtly style so that he could eventually perform at church, in an aristocratic chamber, or at the opera theater. Thus training in partimenti was practical, not theoretical.

By the eighteenth century, the best conservatories found that they could supplement their income by hiring out their well-trained young musicians. This income made possible the recruitment of ever more illustrious teachers, with the result that the Italian conservatories became magnets for talented students and teachers from all over Europe. The conservatories began accepting paying students, and slowly transformed into institutions much like the music conservatories of today.

Gjerdingen edits the web-based series Monuments of Partimenti, which is funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, produced at Northwestern's School of Music, and hosted by Northwestern University. The series provides free access to the partimento repertory and to the sound files for Music in the Galant Style in hopes of encouraging research into the music-cognitive world of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century musicians. All material in the series is in the public domain and may be freely copied and redistributed. The series may be found at the Monuments of Partimenti website.

Reprinted from Northwestern University site.

—Robert O. Gjerdingen, Northwestern School of Music

European court musicians were trained in partimenti, or instructional basses, from the late 1600s until the early 1800s. Partimenti had their greatest influence first in Italian conservatories, especially at Naples, and then later at the Paris Conservatory, where the principles of the "Italian school" continued to be taught far into the twentieth century. Because learning the Italian style of music was a priority for almost any eighteenth-century musician, many well-known non-Italian composers, including Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Mozart, also studied or taught partimenti.

The oldest Italian conservatories were not established to conserve music. They were charitable religious institutions where orphans and foundlings would be taught trades. In a society where family connections and social rank were all-important, an orphan needed a marketable skill in order to make his way in the world. It was not enough to learn "about" music. The child needed to become fluent in the courtly style so that he could eventually perform at church, in an aristocratic chamber, or at the opera theater. Thus training in partimenti was practical, not theoretical.

By the eighteenth century, the best conservatories found that they could supplement their income by hiring out their well-trained young musicians. This income made possible the recruitment of ever more illustrious teachers, with the result that the Italian conservatories became magnets for talented students and teachers from all over Europe. The conservatories began accepting paying students, and slowly transformed into institutions much like the music conservatories of today.

Gjerdingen edits the web-based series Monuments of Partimenti, which is funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, produced at Northwestern's School of Music, and hosted by Northwestern University. The series provides free access to the partimento repertory and to the sound files for Music in the Galant Style in hopes of encouraging research into the music-cognitive world of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century musicians. All material in the series is in the public domain and may be freely copied and redistributed. The series may be found at the Monuments of Partimenti website.

Reprinted from Northwestern University site.

—Robert O. Gjerdingen, Northwestern School of Music